Writing a Lexer in Go with LexMachine

This article is about lexmachine, a library I wrote to help you write great lexers in Go. If you are looking to write a golang lexer or a lexer in golang this article is for you.

A lexer is a software component that analyzes a string and breaks it up into its component parts. Each part is tagged with what type of thing it is. This is called lexical analysis. For natural languages (such as English) lexical analysis can be difficult to do automatically but is usually easy for a human to do. Let's look at an example of lexically analyzing the following English sentence often used in typing practice (because it uses every letter in the alphabet).

The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.

The sentence breaks down into individual word each of which has a part of speech

<article>, "The"

<adjective>, "quick"

<adjective>, "brown"

<noun>, "fox"

<verb>, "jumped"

<adverb>, "over"

<article>, "the"

<adjective>, "lazy"

<noun>, "dog"

Note, the word "over" can actually be either a preposition or an adverb. In this case the context of the sentence (it modifies the verb) makes it an adverb. Many words in natural languages have this property where the context of the overall sentence or paragraph determines the role they play in the sentence.

Luckily, the situation is much simpler for computer languages. Most compilers, which are programs that translate computer languages into other computer languages, start by lexically analyzing their input. They can also be used in a number of other scenarios where a program needs to understand data in textual forms.

In this article, I am going to write and explain a lexer for the

graphviz dot

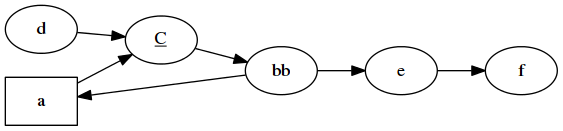

language. graphviz is a tool to

visualize graphs.

graphviz takes a string such as:

digraph {

rankdir=LR;

a [label="a" shape=box];

c [<label>=<<u>C</u>>];

b [label="bb"];

a -> c;

c -> b;

d -> c;

b -> a;

b -> e;

e -> f;

}

And produces :

Lexing Graphviz's dot language

Before one can "lex" (short for lexically analyze) a language one needs to know what it is made up of. English is made up of punctuation marks, nouns, verbs and that sort of thing. Computer languages also have punctuation but also have keywords, strings, numbers, comments and so forth.

When a lexer splits up a string into parts the parts are called tokens. The process of splitting up is also called tokenizing. Let's take a look at how the previous example would get tokenized:

Type | Lexeme

-------------------

DIGRAPH | "digraph"

LCURLY | "{"

ID | "rankdir"

EQUAL | "="

ID | "LR"

SEMI | ";"

ID | "\"a\""

LSQUARE | "["

ID | "label"

EQUAL | "="

ID | "a"

ID | "shape"

EQUAL | "="

ID | "box"

RSQUARE | "]"

SEMI | ";"

ID | "c"

LSQUARE | "["

ID | "<label>"

EQUAL | "="

ID | "<<u>C</u>>"

RSQUARE | "]"

SEMI | ";"

ID | "b"

.

.

.

RCURLY | "}"

Note, that like when the English sentence was analyzed, spaces, newlines, tabs and other extraneous characters were dropped. Only the syntactically important characters are output.

Each token has two parts: the type and the lexeme. The type indicates the role the token plays. The lexeme is the string the token was extracted from.

Specifying Tokens

To specify how a string should be tokenized a formalism called regular expressions is used. If you don't already know about regular expressions you could start with the Wikipedia page. For a more advanced introduction see Russ Cox's articles or Alex Aiken's video lectures on the subject.

To review, a regular expression is a way of specifying a "pattern" which

matches certain strings. For instance, a+b*a matches aaa and abbbba but

not aab. To see why, note that the pattern says a string must start with 1 or

more a characters. So all three strings aaa, abbbba and aab satisfy the

first requirement. Next, the pattern says a string can have 0 or more b

characters. The first string, aaa has none (and that is ok). The second

string, abbbba has 4 b characters. The third string, aab has 1 b. So all

three strings satisfy the second requirement. Finally the pattern says a string

must end in an a. The first and the second string both end in a. However,

the third string, aab, does not. Therefore, the first and second strings match

the pattern but the third string does not.

The Token's for the dot Language

The dot language has keywords, punctuation, comments, and a rather unusual

definition for identifier (called ID). In the listing below, the token type is

on the left side and the regular expression or literal (in quotation marks) is

on the right.

NODE = "node"

EDGE = "edge"

GRAPH = "graph"

DIGRAPH = "digraph"

SUBGRAPH = "subgraph"

STRICT = "strict"

LSQUARE = "["

RSQUARE = "]"

LCURLY = "{"

RCURLY = "}"

EQUAL = "="

COMMA = ","

SEMI = ";"

COLON = ":"

ARROW = "->"

DDASH = "--"

COMMENT = (/\*([^*]|[\r\n]|(\*+([^*/]|[\r\n])))*\*+/)|(//.*$)

ID = ([a-zA-Z_][a-zA-Z0-9_]*)|("([^\"]|(\\.))*")|ID-HTML

Every token type but ID and COMMENT are literals: either a keyword or a

punctuation mark. A comment is defined by a complicated regular expression which

defines "c-style" range comments or line comments. Since the comment expression

is defined by a regular expression no nesting is allowed.

The ID token is more complicated. It consists of three parts:

-

The "usual form" as a name

[a-zA-Z_][a-zA-Z0-9_]*. The pattern means a letter (lower case or capital) or underscore followed by 0 or more letters, numbers, or under-scores. -

A string,

"([^\"]|(\\.))*". Thus"\\\""and"asdf\""are valid but"\\""is not. -

A HTML string, which is non-regular (specified here in BNF):

CHAR = [^<>] ID-HTML = IdHTML IdHTML : Tag ; Tag : < Body > ; Body : CHAR Body ; | Tag Body | e // denotes epsilon, the empty string ;Thus

<<xyz<xy>xyz><asdf>>is valid but<<>is not

The reason the HTML string is not-regular (and therefore cannot be matched by

regular expressions) is the angle brackets, < and >, have to be properly

matched. That is, every opening bracket < must be matched with a closing

bracket >. This is not possible to specify regular expressions because they

cannot "count." For a formal explanation see the Pumping

Lemma.

Consequences of Non-Regular Tokens

If all tokens were regular (that is specifiable by a regular expression) then

the full implementation of the lexer could be generated from the regular

expressions for each of the tokens. Since the dot language contains at least

one token which is non-regular, special consideration needs to be taken.

This turns out to be a fairly common situation in lexer implementation. For

instance, if you want to support c-style comments such as /* comment */ which

support properly nested comments /* asdf /* asdf */ asdf*/ then the comment

token will no longer be regular. Furthermore, many languages (such as C)

require collaboration between the parser and lexer to properly identify whether

symbols should be variable names or type names. This can also introduce a degree

of non-regularity.

Thus, to properly lexically analyze such languages our framework must have an "escape hatch" that allows the analysis of non-regular tokens on demand while still leveraging theory for most of the work.

The LexMachine

To create a lexer for the dot language I am going to use

lexmachine a library I wrote for

creating lexers. lexmachine handles all the tricky bits of converting regular

expressions into Non-Deterministic Finite Automata (NFA) and using the the NFA

to tokenize strings. It also provides the aformentioned "escape hatch" to deal

with non-regular Token specifications.

Let's get started!

The Implementation

As a reminder, the implementation is written in Go. In your workspace, create a new package called dot:

$ mkdir dot

$ cd dot

Now create a file for the lexer:

$ touch lexer.go

All of the code for the lexer is going in lexer.go.

Preamble

To begin, put in the package directive and import the lexmachine and

machines packages. I also import the standard library packages fmt and

strings.

package dot

import (

"fmt"

"strings"

)

import (

lex "github.com/timtadh/lexmachine"

"github.com/timtadh/lexmachine/machines"

)

Note how I group the imports. In general, have three groups of imports. The first group is for standard library packages, the second for third party, and the third group is for other packages in your code.

Defining the Tokens

Next, I create global variables and initialize them. They contain the literal

tokens, the keywords, the token names, and a mapping from the names of the

tokens to their type ids. Finally, there is a variable Lexer *lex.Lexer which

will hold our Lexer object once constructed.

var Literals []string // The tokens representing literal strings

var Keywords []string // The keyword tokens

var Tokens []string // All of the tokens (including literals and keywords)

var TokenIds map[string]int // A map from the token names to their int ids

var Lexer *lex.Lexer // The lexer object. Use this to construct a Scanner

To initialize the lists of tokens we are going to need a function. The reason is

although, Literals and Keywords could be defined in place the rest of the

variables cannot be.

func initTokens() {

Literals = []string{

"[",

"]",

"{",

"}",

"=",

",",

";",

":",

"->",

"--",

}

Keywords = []string{

"NODE",

"EDGE",

"GRAPH",

"DIGRAPH",

"SUBGRAPH",

"STRICT",

}

Tokens = []string{

"COMMENT",

"ID",

}

Tokens = append(Tokens, Keywords...)

Tokens = append(Tokens, Literals...)

TokenIds = make(map[string]int)

for i, tok := range Tokens {

TokenIds[tok] = i

}

}

Right now, the initTokens() function is not being called. Later, I will show

you how to call it on package initialization inside of an init function.

Defining the Lexer

Creating a new lexer object is straight forward.

lexer := lex.NewLexer()

The Lexer object has three methods:

func (self *Lexer) Add(regex []byte, action Action)

func (self *Lexer) Compile() error

func (self *Lexer) Scanner(text []byte) (*Scanner, error)

The Add method is what we are interested in right now. It adds a new token to

the lexer. The token is defined by a pattern expressed as a regular expression

and an Action function. When the pattern is matched the Action function gets

called.

type Action func(scan *Scanner, match *machines.Match) (token interface{}, err error)

An Action takes a *Scanner (which is a object which is scanning a particular

string using the *Lexer object), and a *Match (which represents the string

that was matched by the Regular expression. It returns a token and an error.

If the token return value is nil, the *Match is skipped. This can be used to

skip whitespace and other things you would rather ignore. Let's go head and code

up the the skip Action:

func skip(*lex.Scanner, *machines.Match) (interface{}, error) {

return nil, nil

}

Super simple! It is a no op!

However, most of the time you will want to create a token. First, we need to

have a *Token object to construct. Luckily, lexmachine defines one (although

you don't have to use it). Let's take a look at the definition:

type Token struct {

Type int // the token type

Value interface{} // a value associate with the token

Lexeme []byte // the string that was matched

TC int // the index (text counter) in the string

StartLine int

StartColumn int

EndLine int

EndColumn int

}

func (self *Token) Equals(other *Token) bool

func (self *Token) String() string

The *Scanner object provides a convience function Token which constructs a

token for you. Here is the definition:

func (self *Scanner) Token(typ int, value interface{}, m *machines.Match) *Token

So, with this in mind, here is a simple Action which will construct a Token

with a string version of the lexeme as the Value.

func token(name string) lex.Action {

return func(s *lex.Scanner, m *machines.Match) (interface{}, error) {

return s.Token(TokenIds[name], string(m.Bytes), m), nil

}

}

The name paramter is the name of the token (eg. COMMENT, ID, STRICT,

{, ...). The token function will constuct a *Token of correct type (eg.

the one you specified with name) and return it.

Adding Patterns to the Lexer

Now that we have Action functions to work with (skip and token) we are

ready to add patterns to the lexer. Since lexmachine is built on automata

theory patterns are matched with these priorities:

-

Patterns match prefixes of string being scanned. Normally, a regular expression matches the entire string or the first substring (depending on the mode). After a prefix is matched, the lexer is restarted at the end of the previously matched prefix and matches another prefix until the string is consumed.

-

Through use of automata theory, all patterns are matched in parallel. Currently,

lexmachineuses an Non-Deterministic Finite Automata (NFA) simulation "under-the-hood" to do the matching. NFA simulations take O(P*S) where S is the size of the string and P is the size of the pattern (or in the case of a lexer the sum of the sizes of all of the patterns). There is a Deterministic Finite Automata (DFA) code generator under development (but not ready at this time) which will be able to generate Go code to lex a string in linear time O(S). -

The pattern which matches the longest prefix is chosen as the "matching pattern". The matching pattern determines which lexing action gets run (and thus what kind of token gets created).

-

In case of tie, the pattern which was defined first is chosen.

Since order that patterns are added to the lexer matters, literals and keywords

should be added first. This is important as other token's patterns (such as

ID) could match them. Since, the literals and keywords are both stored in

their own lists this is easy to do in a loop:

for _, lit := range Literals {

r := "\\" + strings.Join(strings.Split(lit, ""), "\\")

lexer.Add([]byte(r), token(lit))

}

for _, name := range Keywords {

lexer.Add([]byte(strings.ToLower(name)), token(name))

}

Note: I add escapes to every character in the literals. So that literals like

[ have patterns such as \[. This ensures those characters (which have

syntactic meaning in regular expressions) are interpreted as themselves.

Otherwise, they would be parsed by the regular expression parser incorrectly.

Second Note: The patterns constructed for the keywords is the lower case version of the token name. I could have had the token names for the keywords be in lower case but it is tradition for token names to be capitalized. This helps distinguish token names from production names in context free grammar.

Adding More Complex Patterns

The simple patterns are now added to the lexer. For the COMMENT and ID

tokens I will add a separate pattern for each of the alternative construction

options:

lexer.Add([]byte(`//[^\n]*\n?`), token("COMMENT"))

lexer.Add([]byte(`/\*([^*]|\r|\n|(\*+([^*/]|\r|\n)))*\*+/`), token("COMMENT"))

lexer.Add([]byte(`([a-z]|[A-Z])([a-z]|[A-Z]|[0-9]|_)*`), token("ID"))

lexer.Add([]byte(`"([^\\"]|(\\.))*"`), token("ID"))

Note: I left out the last form of ID the HTML string. We will get back to that

in a second. The final pattern to add is for whitespace: spaces, tabs, newlines,

and carriage returns. I don't want tokens produced for these characters to I

will use the skip function as the lexer Action:

lexer.Add([]byte("( |\t|\n|\r)+"), skip)

Using the "Escape Hatch"

Now, to deal with the third form of the ID token: the HTML string. I need a

pattern that fires when the beginning of the string is found. This is easy as

the HTML strings always start with a < character and the < is not found

elsewhere in the language. Then, I write a very special Action function. It

turns out, that Actions are allowed to make modifications to the internal

state of the *Scanner. In particular they are allowed to change where the

index into the string being tokenized is located. That index is called the text

counter and is stored in the TC variable. Let's take a look at what *Scanner

exports:

type Scanner struct {

Text []byte

TC int

// contains filtered or unexported fields

}

func (self *Scanner) Next() (tok interface{}, err error, eof bool)

func (self *Scanner) Token(typ int, value interface{}, m *machines.Match) *Token

The Text variable can be read but you should not modify it. Modifying it will

have no effect on the tokenization as the NFA simulation keeps its own pointer

to the text being scanned. The TC variable is the text counter and we can both

read and write it inside of an Action. What this allows us to do is find the

starting point of an HTML string with the pattern < and then scan along

manually counting the opening and closing angle brackets. Once, the initial open

bracket has been closed by a matching > the HTML string has been found.

The only trick is we need to keep track of the text counter and update it. We

also have to update the *Match object to contain the correct values for the

end lines and columns for our token.

Let's see how it works:

lexer.Add([]byte(`\<`),

func(scan *lex.Scanner, match *machines.Match) (interface{}, error) {

str := make([]byte, 0, 10)

str = append(str, match.Bytes...)

brackets := 1

match.EndLine = match.StartLine

match.EndColumn = match.StartColumn

for tc := scan.TC; tc < len(scan.Text); tc++ {

str = append(str, scan.Text[tc])

match.EndColumn += 1

if scan.Text[tc] == '\n' {

match.EndLine += 1

}

if scan.Text[tc] == '<' {

brackets += 1

} else if scan.Text[tc] == '>' {

brackets -= 1

}

if brackets == 0 {

match.TC = scan.TC

scan.TC = tc + 1

match.Bytes = str

return token("ID")(scan, match)

}

}

return nil,

fmt.Errorf("unclosed HTML literal starting at %d, (%d, %d)",

match.TC, match.StartLine, match.StartColumn)

},

)

Here, I defined the action in-line since it will not be reused using Go's

support for anonymous functions. The text counter, scan.TC, is initially

pointing at the character directly following the matched pattern. Thus, the

bracket count in brackets is initialized to 1.

When brackets reaches 0 through incrementing and decrementing everytime a

< or > is seen the match is found. When the match is found, the scan.TC

variable must be updated to communicate back to the scanner where to look

for the next token. The *Match is also updated to reflect the full lexeme that

was found. Finally, an ID token is constructed using the token function.

If the function runs out of text before brackets reaches 0 an error is

returned reporting an unclosed HTML literal.

Compiling the NFA

The last step in *Lexer construction is to compile the NFA. This will be done

automatically when a *Scanner is constructed to tokenize the string. However,

we can have the NFA precomputed by calling Compile. This is important so that

we don't spend time parsing regular expressions every time we want to lex a

string

err := lexer.Compile()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return lexer, n

Putting it all Together

// Creates the lexer object and compiles the NFA.

func initLexer() (*lex.Lexer, error) {

lexer := lex.NewLexer()

for _, lit := range Literals {

r := "\\" + strings.Join(strings.Split(lit, ""), "\\")

lexer.Add([]byte(r), token(lit))

}

for _, name := range Keywords {

lexer.Add([]byte(strings.ToLower(name)), token(name))

}

lexer.Add([]byte(`//[^\n]*\n?`), token("COMMENT"))

lexer.Add([]byte(`/\*([^*]|\r|\n|(\*+([^*/]|\r|\n)))*\*+/`), token("COMMENT"))

lexer.Add([]byte(`([a-z]|[A-Z])([a-z]|[A-Z]|[0-9]|_)*`), token("ID"))

lexer.Add([]byte(`"([^\\"]|(\\.))*"`), token("ID"))

lexer.Add([]byte("( |\t|\n|\r)+"), skip)

lexer.Add([]byte(`\<`),

func(scan *lex.Scanner, match *machines.Match) (interface{}, error) {

str := make([]byte, 0, 10)

str = append(str, match.Bytes...)

brackets := 1

match.EndLine = match.StartLine

match.EndColumn = match.StartColumn

for tc := scan.TC; tc < len(scan.Text); tc++ {

str = append(str, scan.Text[tc])

match.EndColumn += 1

if scan.Text[tc] == '\n' {

match.EndLine += 1

}

if scan.Text[tc] == '<' {

brackets += 1

} else if scan.Text[tc] == '>' {

brackets -= 1

}

if brackets == 0 {

match.TC = scan.TC

scan.TC = tc + 1

match.Bytes = str

return token("ID")(scan, match)

}

}

return nil,

fmt.Errorf("unclosed HTML literal starting at %d, (%d, %d)",

match.TC, match.StartLine, match.StartColumn)

},

)

err := lexer.Compile()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return lexer, nil

}

Initializing the Package

To ensure that the regular expressions are only compiled once, we are going to

call initLexer once at the start of the program. To do this we put the call

inside an init function.

Init functions get run once on program start up.

// Called at package initialization. Creates the lexer and populates token lists.

func init() {

initTokens()

var err error

Lexer, err = initLexer()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

And that is it. Here is the source code for the full lexer.

Using the Lexer

Let's put it all together. Here is a simple example which uses the lexer:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"log"

)

import (

"github.com/timtadh/dot"

lex "github.com/timtadh/lexmachine"

)

func main() {

s, err := dot.Lexer.Scanner([]byte(`digraph {

rankdir=LR;

a [label="a" shape=box];

c [<label>=<<u>C</u>>];

b [label="bb"];

a -> c;

c -> b;

d -> c;

b -> a;

b -> e;

e -> f;

}`))

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

fmt.Println("Type | Lexeme | Position")

fmt.Println("--------+------------+------------")

for tok, err, eof := s.Next(); !eof; tok, err, eof = s.Next() {

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

token := tok.(*lex.Token)

fmt.Printf("%-7v | %-10v | %v:%v-%v:%v\n",

dot.Tokens[token.Type],

string(token.Lexeme),

token.StartLine,

token.StartColumn,

token.EndLine,

token.EndColumn)

}

}

Output:

Type | Lexeme | Position

--------+------------+------------

DIGRAPH | digraph | 1:1-1:7

{ | { | 1:9-1:9

ID | rankdir | 2:3-2:9

= | = | 2:10-2:10

ID | LR | 2:11-2:12

; | ; | 2:13-2:13

ID | a | 3:3-3:3

[ | [ | 3:5-3:5

ID | label | 3:6-3:10

= | = | 3:11-3:11

ID | "a" | 3:12-3:14

ID | shape | 3:16-3:20

= | = | 3:21-3:21

ID | box | 3:22-3:24

] | ] | 3:25-3:25

; | ; | 3:26-3:26

ID | c | 4:3-4:3

[ | [ | 4:5-4:5

ID | <label> | 4:6-4:12

= | = | 4:13-4:13

ID | <<u>C</u>> | 4:14-4:23

] | ] | 4:24-4:24

; | ; | 4:25-4:25

ID | b | 5:3-5:3

[ | [ | 5:5-5:5

ID | label | 5:6-5:10

= | = | 5:11-5:11

ID | "bb" | 5:12-5:15

] | ] | 5:16-5:16

; | ; | 5:17-5:17

ID | a | 6:3-6:3

-> | -> | 6:5-6:6

ID | c | 6:8-6:8

; | ; | 6:9-6:9

ID | c | 7:3-7:3

-> | -> | 7:5-7:6

ID | b | 7:8-7:8

; | ; | 7:9-7:9

ID | d | 8:3-8:3

-> | -> | 8:5-8:6

ID | c | 8:8-8:8

; | ; | 8:9-8:9

ID | b | 9:3-9:3

-> | -> | 9:5-9:6

ID | a | 9:8-9:8

; | ; | 9:9-9:9

ID | b | 10:3-10:3

-> | -> | 10:5-10:6

ID | e | 10:8-10:8

; | ; | 10:9-10:9

ID | e | 11:3-11:3

-> | -> | 11:5-11:6

ID | f | 11:8-11:8

; | ; | 11:9-11:9

} | } | 12:1-12:1

Conclusion

Believe it or not 3500 words later, we have only scratched the surface on this topic. Testing, custom token representations, automata construction, and more will have to wait for another post. While still in an early state I hope you find lexmachine useful and this article helpful for constructing lexers whatever language you are using.